We got together with folks from Linkedin to discuss what makes a good UX portfolio and how you can create one that recruiters will love.

Job hunting is one of the most stressful experiences we can go through. The uncertainty combined with pressure to at least secure call backs can mount to crushing levels. Designers everywhere pour sweat into the search for the perfect UX portfolio – so we thought we might help them out a bit.

That’s why we invited Kristine Yuen, Design Manager, and Ulrika Andersson, Senior UX Designer, for a chat. We wanted to know what they look for in a candidate’s UX portfolio, as well as their opinion on how designers can get it right.

The result was an illuminating UX talk that had our audience on the edge of their seat, with pens at hand ready for note-taking. Let’s check it out!

LinkedIn explains how to make a great UX Design portfolio.

You can download the deck here https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/embed_code/key/g1irAUBNoYZwZ7Posted by Justinmind Prototyping Tool on Wednesday, 25 September 2019

A UX design portfolio consists of a series of case studies on previous projects. These aim to demonstrate how you approach the UX process, and who you are as a designer. Our speakers were keen on conveying how important these case studies are, as recruiters won’t simply take notice of your design outputs. They also care about how you think.

There are many ways designers can go about creating their portfolio – and many different elements to include in them. With that said, Kristine takes us on a walk through the most common elements that make up a designer portfolio.

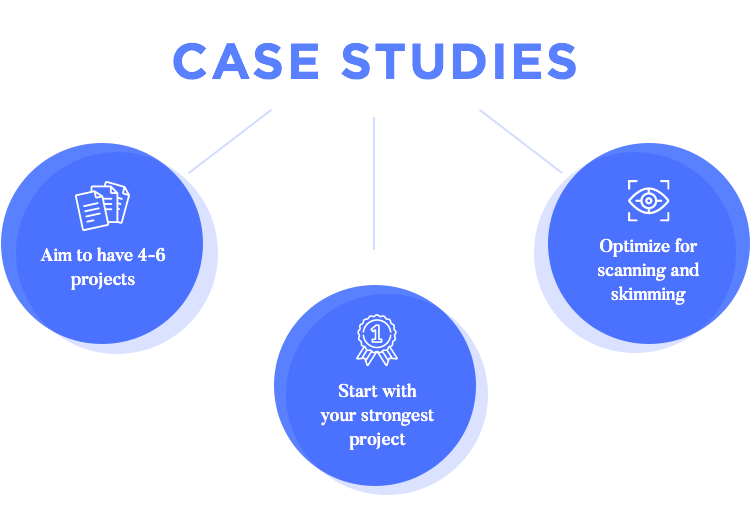

The bulk of your portfolio is likely to be your case studies. Kristine recommends including 4-6 case studies – it should be a nice and even number that allows for an overview of your skills. You can always include more than 6 cases, but you take the risk of overwhelming the recruiter and diluting your strong points.

One of Kristine’s general recommendations is that you present your strongest, most comprehensive case first. This will help you make a good first impression, and mitigate the risk of recruiters only looking at your first case. Some choose to present their most recent case first, but you really want to potentialize that first impact.

It is also important that you optimize the cases for scanning, as most recruiters have a long list of candidates and limited time to analyze each portfolio – but we’ll get to that later on.

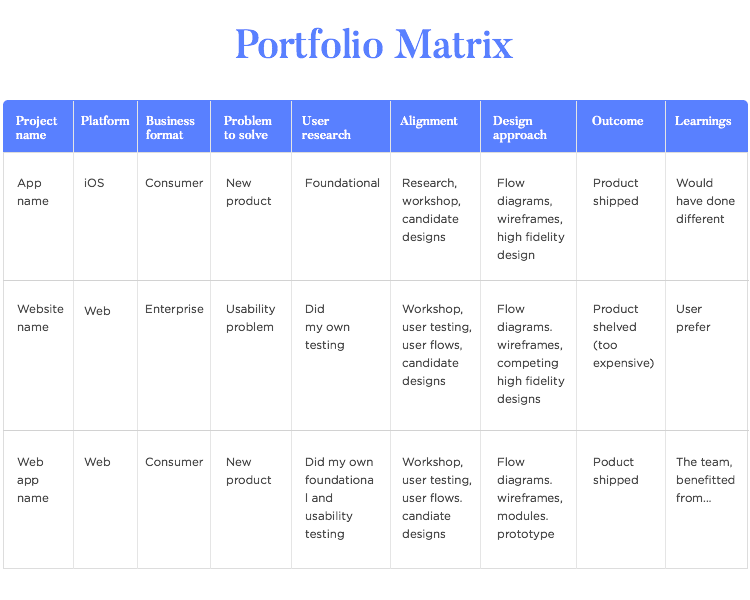

As a UX designer, you’re likely to have more than 4 or 6 projects under your belt. So how to decide which ones to include? Luckily, our speaker Ulrika came up with the portfolio matrix – and we are so happy she did.

The idea is that you list out your projects and analyze them according to a group of parameters. Here are the ones recommended by Ulrika:

- Project name

- Platform

- Business format

- Problem to solve

- User research

- Alignment

- Design approach

- Outcome

- Learnings

Once you list them all and the corresponding information as well, you’ll begin to notice strong points. This can be as simple as having many different projects that were focused on solving usability issues, or lots of experience with consumer-oriented products.

The way this matrix helps you to choose the right projects for your portfolio is that by looking at these strong points (and the weak points as well), you can balance them out. By choosing the right projects, you can showcase all of your top skills and mitigate those that aren’t as developed.

This section is a personal favorite of our speaker, Kristine. This is where you can really show who you are as an individual and not just as an employee. You can have some fun with it and try to include a snapshot of your personality such as the things that motivate you, what got you into design or what your passions are.

This shouldn’t be a repetition of your CV. That information can be easily found elsewhere and is a waste of an opportunity to introduce yourself on a more personal level. This is a great area to humanize yourself and your portfolio – recruiters like getting a feel of the personality behind the design.

It’s easy to get stuck in this section. After all, people are complex beings and it can be hard to define what part of you to convey here. In the face of this challenge, Kristine recommends starting out with a simple outline.

Before trying to get the specifics down on paper, think in terms of categories on a high level. So, instead of thinking about including either your love of photography or painting – just consider that you will have a “passions” category. Other possible categories include experiences or skills.

The second step is starting your narrative. As you think about what you’ll say and how you’ll say it, try to include your previous experiences – especially if you’re a career changer. Just like Kristine herself, who started out in business administration before leaping to design, many have a change of direction in their career.

In these cases, it’s wonderful to share the story behind that change. It will be a bright window into who you are and elaborate on an interesting period of your life – but it also gives you an opportunity. By going into your previous profession, you can put the transferable skills that you took with you from that profession into design.

This section needs to be relatable. Try to use the proper design industry language, include personal experiences and make it so that the person who reads feel like they know you a little better afterwards. The transferable skills factor can make your story very relatable to people who went through similar experiences, for example.

This should be by far the most straightforward part of the portfolio. The key to getting this right is location: recruiters should never have to look for your contact information. Kristine recommends placing your information on the footer of every screen. Another important thing is to check that your information is up-to-date, as well as checking for broken links.

Kristine shares that she is often asked about the right platform for designers, and if they should code their own portfolios. That is entirely up to the designer but she does point out that, although coding can be a real plus if you wish to be known for your coding skills, it’s not a real requirement or necessity.

That is, in part, because designers have plenty of tools available to them that mind the coding, while designers are free to mind the actual design. Here are the main platforms you can go for.

These include tools like Wix or SquareSpace, and are the most popular platform for portfolios. They are largely popular because they offer templates that are already structured for portfolios, which can be adapted to suit your style.

This type of platform tends to work better for lengthy content, such as portfolios that are more research-oriented. These include WordPress and Medium, and represent a good platform if you want to highlight your writing skills.

Platforms like Behance and Dribbble are more visual in nature, and can be used for UX design portfolios. In these platforms, however, it can be more difficult to offer context and formulate the full case studies. They are recommended for graphic or visual designers.

Kristine suggests that designers approach the making of their portfolio like they would a new UX project. That means that before you get to actually making the portfolio, you should sketch it out. This should help you get clearer on what content and information each case study will include and what it should look like.

It’s recommendable to look for a template after this sketching is done. As Kristine shared with us, it’s not uncommon for designers to choose a template and spend lots of time trying to adapt it to their portfolio – only to conclude it isn’t suitable. Getting your mind set on a template is dangerous if you’re not sure of what kind of structure your case studies will need.

A case study should be a shared story of your leadership, our speaker Ulrika says – and we fully agree. Your case studies should tell the story of how you helped your previous stakeholders find a solution to a problem.

As most experienced designers will know, UX teams usually start out not actually knowing what they will design or build. There’s a huge amount of work that goes into defining the problem and making a long list of possible solutions – this process can be both demanding and confusing.

“I’m looking for signs that you can provide leadership, that you can bring the team with you.”

Ulrika Andersson - Senior UX designer at Linkedin

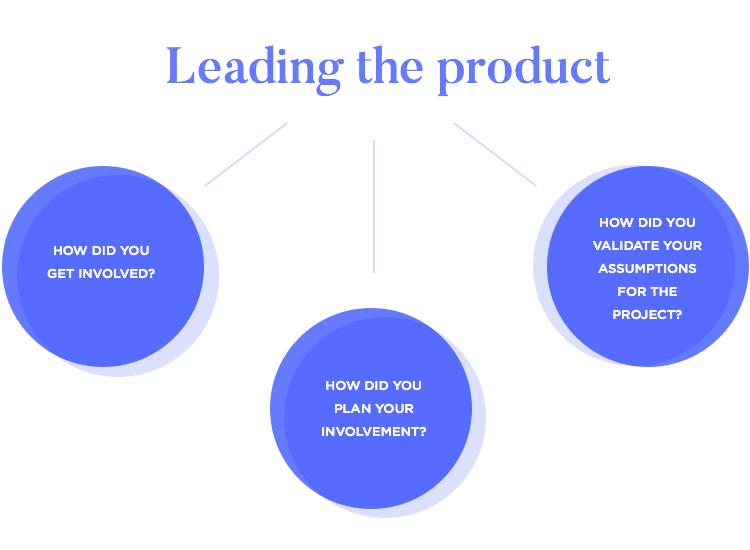

So how do you illustrate your part in that process? Ulrika shares some of the crucial information you need to include in the case studies to illustrate the part you played in finding the right solution.

How did you get involved?

Pointing out that you noticed an issue and made a proposal for a solution can make a good impression. Saying that you were assigned to the task is also perfectly acceptable.

How did you plan your involvement?

This can be a way for you to show how you structured and planned the project. Things like setting up timelines, planning for future deliverables and defining milestones are all positive points.

How did you validate your assumptions for the project?

For Ulrika, this is all about your reasoning and thinking. It should show how you went about making decisions as the project progressed. Things like competitor analysis, searching for written studies, getting quantitative data and testing are all great points to make.

As Ulrika wisely puts it, the team is the most important asset you can have. A good leader takes the experiences and skills of team members and uses them as assets. This comes with many implications, such as allowing the team the freedom to contribute at every step of the design process.

Even if you weren’t the team manager, you can still showcase your leadership skills. For example, how did you help the manager achieve the task? How did the manager become comfortable with giving you the freedom to design and look for answers?

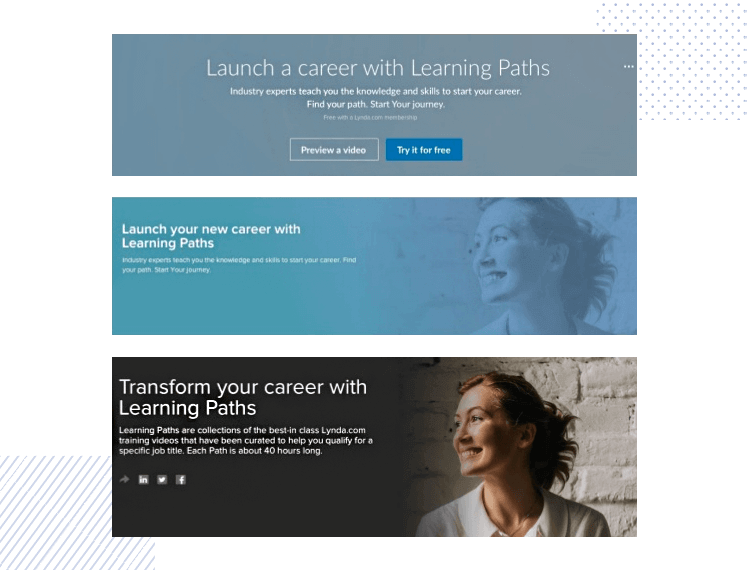

You can also include a view into the part that deliverables played in the team. For example, a deliverable that helped align the team. It could also be multiple variations of the same design with an explanation of how the team selected the best one – which brings us to the next point.

Deliverables can be a great way to show iteration and team dynamics. Showing variations of the same design is great, because it allows you to walk the recruiter through the thinking of the team. How did everyone come to a conclusion on the best alternative? What parameters were used in the decision-making?

Kristine also points out that you should be prepared to go over these verbally in an interview. Recruiters can take an interest on the underlying reasons for the design, and may want to chat about how you chose one over the other.

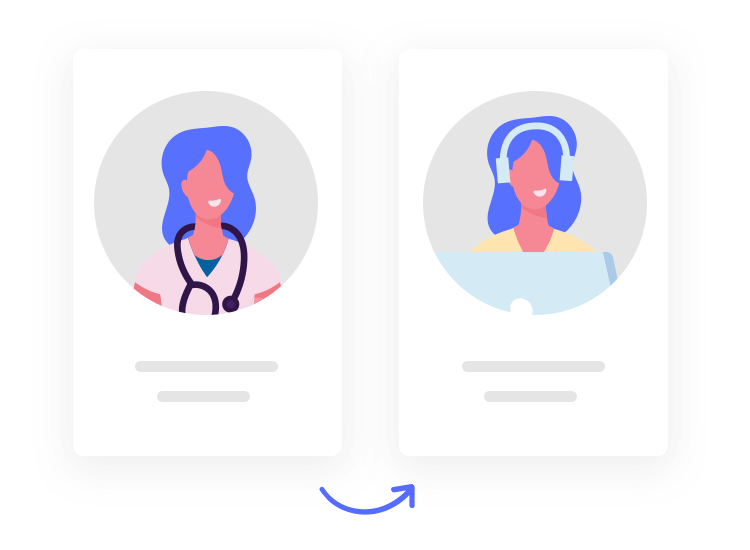

Ulrika shares with us that career changers want to use their previous career to show they are fit to be a designer. Much like the example of a nurse turned designer, there are many different backgrounds that could boost your skills as a designer.

It’s important to keep in mind that recruiters only have 2-3 minutes to dedicate to your UX portfolio. This means that if you have two careers, you want to help the recruiter interpret your experience, your story. It needs to present the key benefits you took with you into the field of design, in a concise way.

That is not to say, however, that you need to completely abandon your previous career. If you want to present a more comprehensive view of both your careers – that is perfectly fine. Ulrika recommends that you create two portfolios: one for the career you had and one for the career you want.

This way, you’ll create two concise portfolios that will keep the attention of the recruiter, effectively telling your UX story better. If you create one portfolio that tries to cover everything, you risk creating something that won’t have a clear focus or will be too dense.

This one can be a bit tricky for those UX designers that don’t want to be perceived as solely visual designers. Even if you want to focus more on the experience design, having strong visuals is still a must.

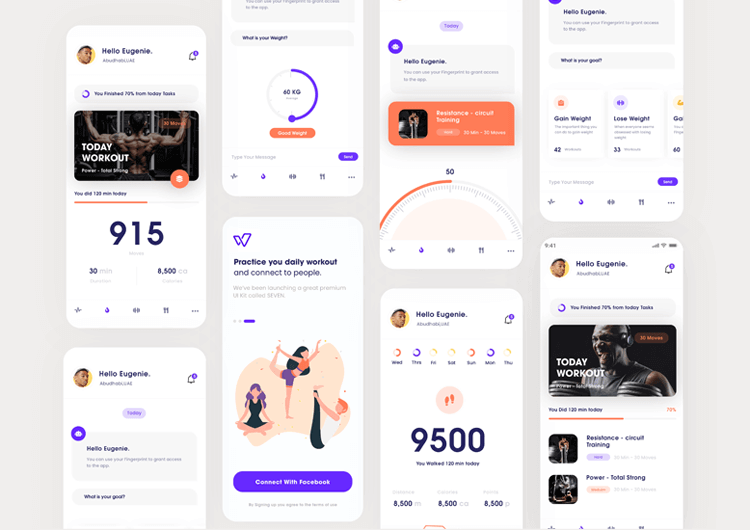

Design by Hesham Mohamed.

Strong visuals make for a big impact on the first impression of your UX portfolio. Kristine admits that having strong visuals is an easy way to get your foot in the door – but it should not be the sole reason you get the job. Let your first impression be a good one, then go on to share who you are and what makes you a good fit.

Your UX portfolio needs to be balanced. On the one hand, you want strong visuals and to show off your previous work. On the other hand, you also want to explain who you are, some of the skills you have and the kind of benefits you bring to the table. Overdoing either, however, is a big no-go.

It’s possible that you have some more visuals that you would like to include, or perhaps a text that goes more in-depth about some research you’ve done. In these cases, Kristine suggests having a separate file that recruiters can look into if they feel a need to.

You want to achieve a balance when presenting all of that to recruiters. In the end, most of them don’t actually read all of the content or look into the details – which takes us to the next point.

Once more, just to really make sure we don’t forget: recruiters have a surplus of applicants, and not enough time to look at each of them closely. That raises the need for your UX portfolio to be scannable by recruiters with a glance.

Kristine recommends that you pull out all the readability tools from your toolbox. The classics include breaking up content into sections with headers, using bold to highlight the key words and making smart use of whitespace. In broad strokes, you should be careful about your emphasis and always offer the eye some relief.

It’s important to recruiters to get a sense of how you make your decisions, how you approach problems. And so, you should aim for showing your reasoning behind every decision in your UX portfolio.

The UX design process can be long and complex, which means that recruiters can’t sit down to read your entire adventure from previous projects. Your UX portfolio should include only the important bits, such as crucial turning points, key findings, or the factors that pushed the design a certain direction.

The case studies in your portfolio can’t go on forever – you have to be concise.

It’s not that uncommon to have a complex project that had many different levels – say, a project that included a web branch and another mobile branch. It’s useful to break those up into two separate case studies, and maximize the impact from both on the portfolio. That way, you get to present all the right information without overwhelming recruiters.

Locking the entire portfolio is discouraging to recruiters. Kristine herself shares that when confronted with a locked portfolio, it’s unlikely she’ll make the effort to gain access – not with a long line of applicants ready to share their work.

It’s okay to lock the parts of your portfolio that you can’t openly share. Even with a partially locked portfolio, it’s a tricky decision to make. Using a partially locked portfolio may offer some setbacks such as recruiters moving on to the next applicant in line.

However, if you’re willing to take that risk, it’s recommended that you make sure your contact information is readily available so recruiters can ask you for the access code.

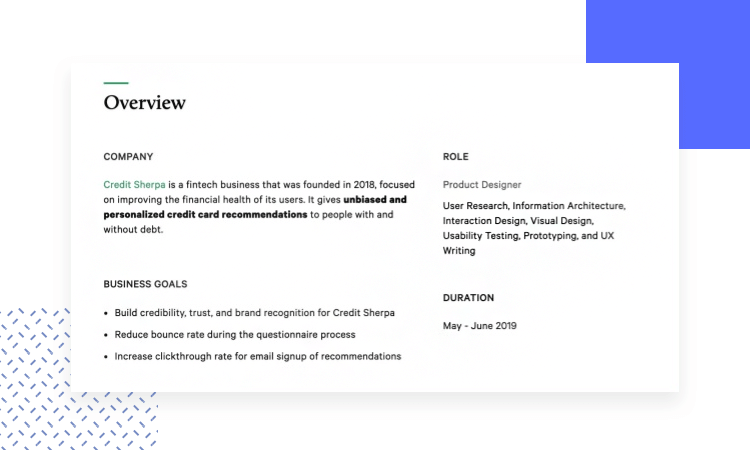

Here’s a very important tip for making your UX portfolio a winner: never skip the context. It’s a vital part of storytelling. After all, a solution is only as impressive as the problem – and without the key basics, your case studies may fall flat.

Having a design in a case study that looks cool isn’t enough. In truth, recruiters won’t be able to understand the significance of the design or the project as a whole without some key pieces of information. With that said, never forget that it must be concise and scannable!

So what kind of information do recruiters need? Aim for the classics: who, what and why.

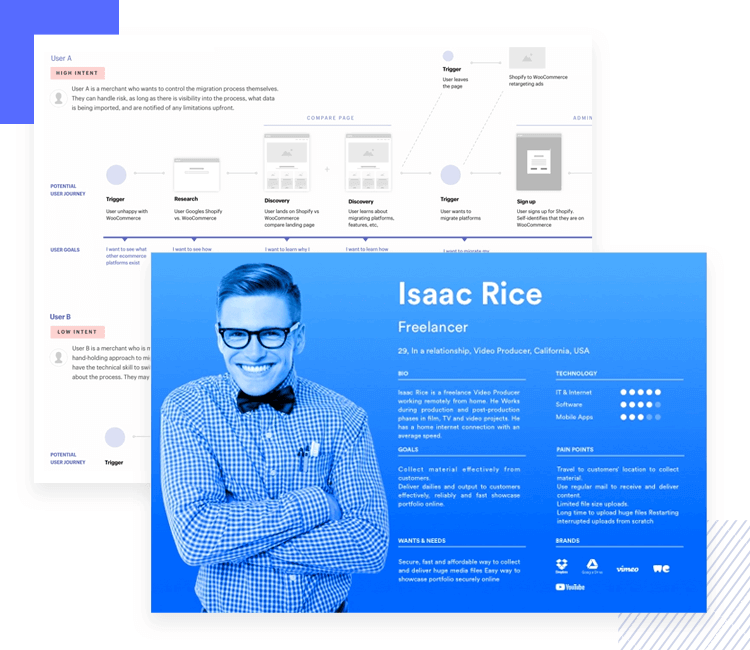

Even if your main area of work wasn’t the research, it’s still important to include it in the case studies. It shows that you understand the role research plays in the UX design game. When done right, your research part of the case study will show that you understand the connection between UX research and user-centric design.

User Journey map by Janna Hagan and user persona by Mohamed Boumaiza.

Try to showcase who the users were, the methods used in the research and what you were hoping to achieve with them. Feel free to credit others who carried out the research with you. UX design is often a team effort!

This part can be found within the research section of the case studies or as its own individual part – both are alright. You’ve got to watch out for elaborating too much on this part, as research is likely to give you many insights into the project.

The key here is going for the bottom line: what insights did you get and how did they shape the design? How did you make the leap from the insight to a decision on the design?

You want to show recruiters that you can analyze the results from research and correctly translate them into tangible changes to the product. This section should show your thinking and reasoning skills – and should be closely linked to your validation and iteration.

It’s potent to show that the design process in any case study wasn’t a straight line – there tend to be many sudden turns involved. Showing iterations is a great thing, because it illustrates how you go about optimizing your work. It’s a tangible result from all your research, and shows the actual impact from all the feedback you got on the design.

Kristine is a big fan of seeing how candidates improved on their design, as well as what kind of things they learned along the way.

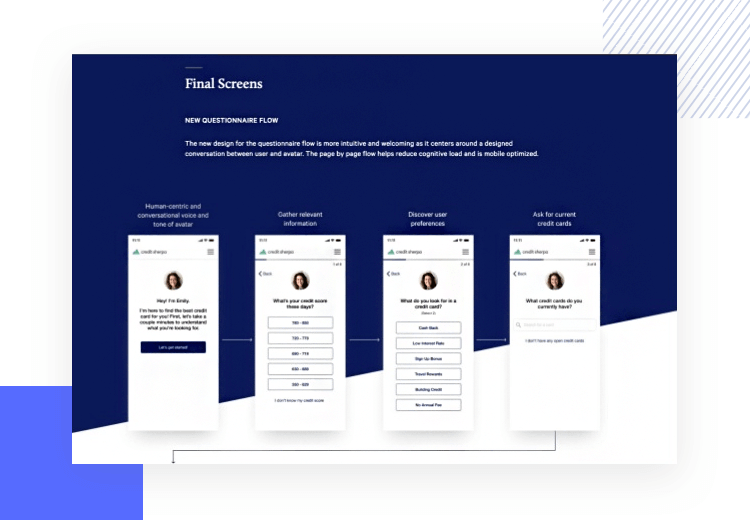

Choosing the right way to show the final solution will depend on you. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all recipe for presenting the work – it’s a matter of preference. Kristine, for example, chooses to put the solution in the end of the case study. This gives her the opportunity to present the situation, the project, and all the necessary context to the reader first.

It’s also a good idea to include a snippet of the finished project at the beginning, leaving the detailed view to the end of the case study. That way, you give the recruiter an idea of where all this is going while not elaborating too much on key areas of the design.

In the end, says Kristine, just do what makes you feel comfortable. It’s not black and white, but rather with plenty of grey so you can present the solution in your own way.

You can include the end-to-end flows, which will give a nice idea into the hard work you put into the planning of the solution. There’s no need to present all the possible user paths – choose the best ones in your opinion. It’s always better to present a high-fidelity representation of your solution!

Kristine is a fan of using GIFs to show her solutions. They play in a loop and mitigate the risk of recruiters not playing a video. Not only that, but they also allow you to show off your animation skills!

Including videos is perfectly acceptable, as long as the video remains entirely focused on the UI. Kristine also points out that it’s important for videos to not have any audio and be on auto play.

Yes, but it has to be perfect. A prototype lets recruiters get into the small details to check that everything was done correctly, opening the door to them identifying even the smallest mistakes.

Quick tip: For truly high-fidelity prototypes, visual editors don’t cut it. Go for a professional prototyping tool instead.

Even small mistakes can damage that first impression you tried so hard to establish with the design of the UX portfolio. On top of that, it also makes it seem as if you hadn’t put that much thought into the solution.

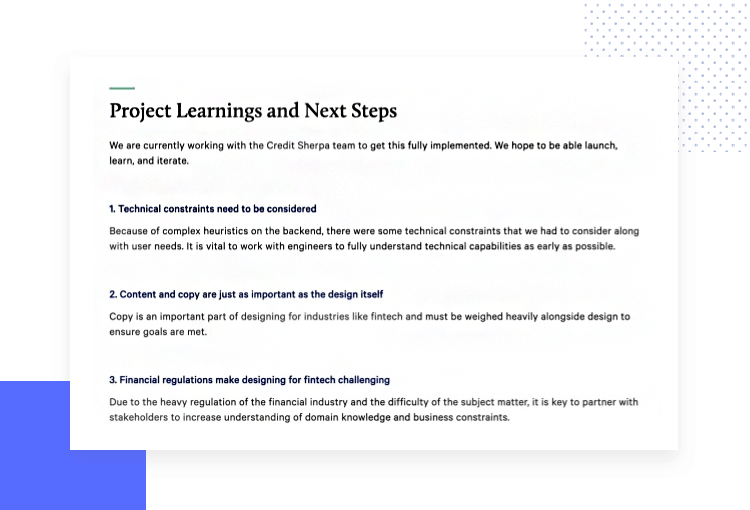

Design is a never-ending process. It implies constant learning and being open to learning is a great asset to any designer. And so, it makes for a perfectly acceptable section in the case studies: what did you learn from that project?

It could be anything new you learned about yourself, about UX in general or about users. You could share how a certain project changed your perspective or perhaps a hard lesson learned.

There’s nothing wrong with recognizing mistakes here, and sharing what it is exactly that they taught you. In fact, the argument could be made that by owning up to your mistakes, you demonstrate that you see these mistakes as learning opportunities and not embarrassments. This is a potent trait in just about any profession out there!

Creating your own UX portfolio isn’t easy. After all, it needs to work as an overview of not just your work but also how you function. It’s all about trying to show how you process information, tackle challenges and think out solutions to problems.

Yes, it’s difficult. But hopefully, our dear speakers Kristine and Ulrika will have helped you formulate and plan out a UX portfolio that ticks all the right boxes. Now, it’s up to you to make sure that your portfolio speaks to who you are, not just as a designer but as an individual as well! Good luck!

PROTOTYPE · COMMUNICATE · VALIDATE

ALL-IN-ONE PROTOTYPING TOOL FOR WEB AND MOBILE APPS

Related Content

Why should you use user personas and how do you create them? Get all the steps to build one, as well as a great example and a list of user persona generators!15 min Read

Why should you use user personas and how do you create them? Get all the steps to build one, as well as a great example and a list of user persona generators!15 min Read UX design books that cover everything from layout design to the theory of user testing. Want to expand your horizons? Check out this awesome list!9 min Read

UX design books that cover everything from layout design to the theory of user testing. Want to expand your horizons? Check out this awesome list!9 min Read UX design portfolios are your chance to showcase your top skills and best work. Check out this post for awesome portfolio examples and websites!10 min Read

UX design portfolios are your chance to showcase your top skills and best work. Check out this post for awesome portfolio examples and websites!10 min Read